Fake reviews - will the FTC's new rules fix the problem?

TL:DR

The Federal Trade Commission is proposing new rules to crack down on fake reviews. Their proposal would target individuals and companies who post fake reviews, not platforms.

This was the same approach the US Government tried with the CAN-SPAM act in 2003. But since the FTC doesn’t have jurisdiction overseas, it didn’t do much to stem the tide of spam.

What ultimately made spam manageable was filtering and verification processes developed by the email providers, who were highly incentivized to solve the problem.

The FTC’s approach to tackling fake reviews suffers from the same problems that hindered the CAN-SPAM act; enforcement against individual fake review posters would be resource intensive, and they don’t have jurisdiction overseas where many fake reviews originate.

Right now, the review platforms don’t have much of an incentive to solve the problem. Amazon makes money from every sale, whether motivated by a fake review or not.

If the Government wants to stop the problem of fake reviews, they need to find a way to hold the platforms accountable, including possible amendments to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

The New Rules

The Federal Trade Commission is getting ready to issue new regulations aimed at cracking down on fake reviews and the companies who post them. We welcome this news, since fake reviews are a large problem that is undermining consumer confidence in e-commerce and putting honest businesses at a disadvantage. But unfortunately, the FTC’s plan targets individual companies that post fake reviews, instead of holding the platforms like Amazon and Google that host them responsible (we’ll address Section 230 later). It is thus unlikely to be effective.

What the CAN-SPAM Act Teaches Us About Fighting Fake Reviews

To understand why the FTC’s proposed fake review rules won’t work, it’s helpful to consider the history of email spam, and how it was ultimately brought under control.

In the early 2000s, the rapid growth of email spam was overwhelming email users. Estimates at the time suggested that 80% or more of the messages a typical email user received were spam. There was a fear that spam would get so bad that it would soon render email itself essentially unusable. The issue was salient enough that in 2003, President George W. Bush signed the CAN-SPAM act into law. This was an attempted legislative fix to the problem of spam, which established some regulations on email marketers and provided for fines and sanctions against individuals and companies that violated them. The CAN-SPAM act may have helped at the margin, but it was insufficient to make a major dent in the spam problem for a number of reasons:

It was inherently resource intensive for the FTC to police the large number of small-scale spammers.

The Federal Trade Commission didn’t have jurisdiction overseas, making it nearly impossible to crack down on spam originating abroad.

It was easy for US-based spammers to move their operations abroad, beyond the reach of the FTC.

CAN-SPAM wasn’t a total failure. For example, its opt-out mandate made it easier to unsubscribe from the email lists of reputable email marketers. But it didn’t turn the tide on spam. What ultimately solved the problem, or at least made it bearable, was the email companies.

Less than a year after the CAN-SPAM act passed, Bill Gates announced at the World Economic Forum that he thought Microsoft would soon make spam emails obsolete. While the part of Gates's proposal to charge for digital postage stamps didn't pan out, he was correct that email platforms would ultimately make the problem of spam manageable. While spam is still with us, unsolicited emails from Nigerian Princes or people pushing cheap Viagra no longer overwhelm inboxes. If they get delivered at all, they are generally sequestered in a spam folder.

What finally reined in spam wasn't the FTC sanctioning individual Nigerian Price email scammers, it was the email providers like Microsoft and Google developing scalable technological solutions to block and filter spam messages. The email providers didn’t do this out of the goodness of their hearts. Rather, they controlled a key piece of internet infrastructure and were merely responding to market incentives. If spam made email unusable, people would stop using their products.

The Platform Incentives of Fake Reviews

The problem of fake reviews is very similar to spam in the early 2000s. Like spam, fake reviews can be posted from anywhere in the world. Like spam, the costs are so low that a huge number of companies and individuals find it worthwhile to engage in. Like spam, the Government’s plan to address the fake review problem by sanctioning individual companies will likely be ineffective due to the global nature of the problem.

What’s different this time are the incentives of the platforms. Microsoft, Google and the other email providers were uniquely well positioned to combat spam and highly incentivized to do so. Review platforms like Amazon are similarly well-positioned to take on the problem of fake reviews, but their incentives to do so are at best murkier.

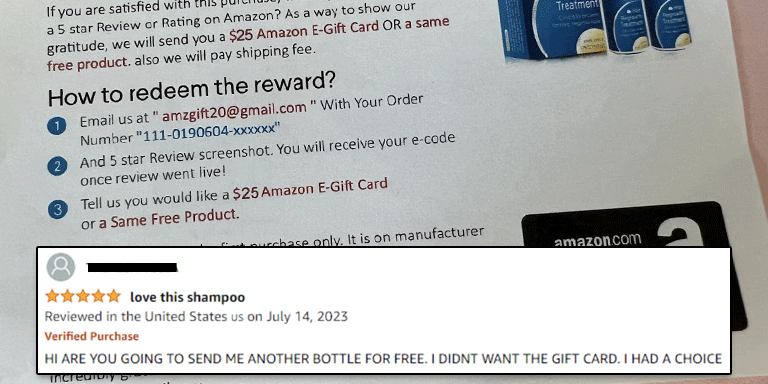

Amazon brags about its efforts to combat fake reviews, but it is obvious to anyone looking that fake reviews are still rampant across the e-commerce platform. 3rd party researchers estimate that as many as 50% of all reviews on Amazon are fake. A PerfectRec employee reported this explicitly incentivized fake review, where an Amazon seller was explicitly offering compensation for favorable reviews, to Amazon on August 8, 2023. It is now August 29th and they have still not taken any action on it.

So what is going on here? Is the company that invented AWS and disrupted retail really incapable of solving the fake review problem? We doubt it. The issue is more likely that the incentives aren’t there. Fake reviews are a little embarrassing for Amazon, but at the end of the day Amazon makes money on each product sold, including when that sales was motivated by a fake review. On top of that, cracking down on fake reviews could increase tensions with Amazon sellers who rely on fake and incentivized reviews to promote their products. This is a similar issue faced by Google, which could crack down on fake reviews featured in shopping ads, but may not want to potentially upset some advertising customers by doing so.

Review platforms could solve the fake review problem. Indeed they are probably the only actors who are well-positioned to do so. The problem is they don’t have sufficient incentives to do so and won’t without new legislation to specifically provide it.

What the Federal Government Should Do Instead

The FTC won’t be able to solve the fake review problem with their current plan to sanction individual companies, but not to hold review platforms accountable. This approach faces the exact same shortcomings as the CAN-SPAM act; policing a huge number of small actors is inherently resource intensive and the FTC does not have jurisdiction overseas. Instead, the FTC should figure out a way to hold review platforms accountable for fake reviews posted on their site. This would upend the current status quo where review platforms tacitly tolerate fake reviews and highly incentivize them to solve the problem, the way the email providers takeled spam. The obvious objection to this proposal is that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 gives internet platforms broad protections against being held liable for 3rd party content posted to their sites. But Congress has carved out exceptions to Section 230 before. As recently as 2018, Section 230 was amended as part of the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act. Congress could and should make another exception to Section 230 allowing the FTC to hold review platforms accountable for fake reviews in order to help restore confidence in e-commerce and protect honest businesses from bad actors abroad.

Public Comment Submitted to the Federal Trade Commission

At PerfectRec, our mission is to make shopping much easier. We believe that fake reviews are a serious problem that is undermining faith in e-commerce and making product discovery harder. On August 20th, we submitted a public comment to the FTC urging them to expand their proposed rules on fake reviews to hold review platforms accountable.

.

Other recommended articles

CHART: Elon Musk net worth and Twitter habit

Chart: Streaming Service Churn Rates

Who is thinking about the Roman Empire?

CHART: The price history of the Samsung Galaxy S, adjusted for inflation

Stay up to date on new products

Get occasional updates about new product releases, interesting product news, and exciting PerfectRec features. No spam. We never share your email.